- This event has passed.

Musician Julian Saporiti approaches refugee storytelling with compassion

By Maddie Browning

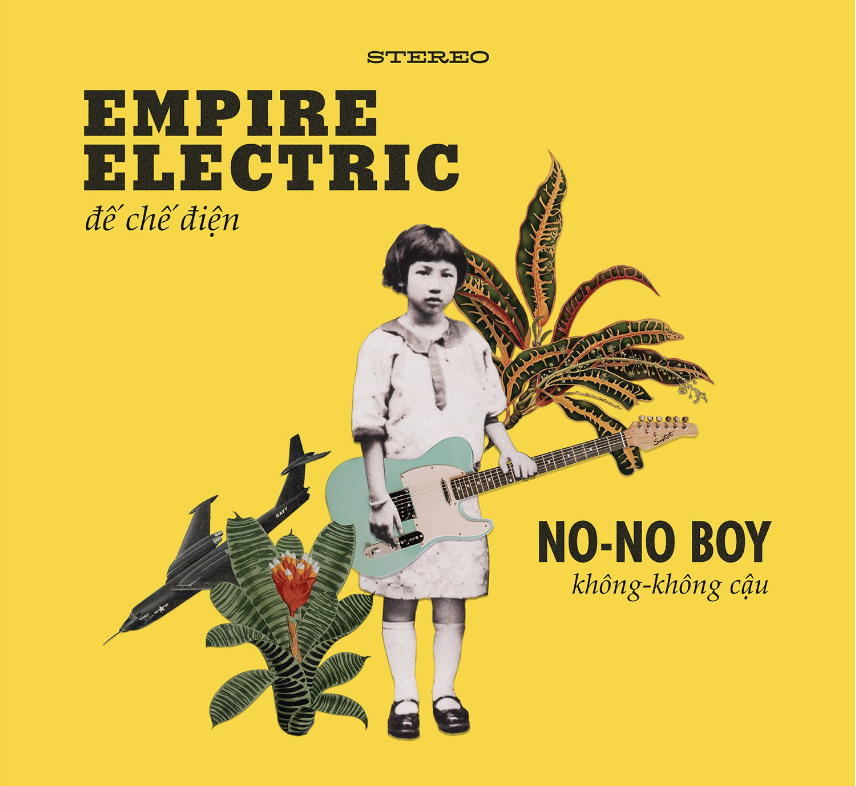

Berklee alum Julian Saporiti releases music inspired by his fieldwork and research on Asian American history under the pseudonym No-No Boy – a reference to John Okada’s novel of the same name.

A selection of his songs and music videos are a part of Emerson Contemporary’s “One Day We’ll Go Home” exhibition on display through December 16.

Emerson Contemporary chatted with Saporiti on Zoom about his favorite musical artists, collaborating on artistic projects with his wife, and checking his privilege with the monks at Blue Cliff Monastery.

EC: What artists are you inspired by?

Saporiti: There’s a painting in the MFA in Boston called “Slave Ship” by [Joseph Mallord William] Turner, and when I was in school at Berklee, I would go see that painting a lot. It’s a really horrible subject matter, it’s this wrecked slave ship, so it’s all these bodies in the ocean but it’s full of [these] beautiful sunset or sunrise colors – oranges and pinks – mixed with the turbulence of the ocean. So that was always super striking, and very similar to a lot of the work that I do, which is dealing with stories of people crossing oceans under not so good circumstances. But that painting, I was always entranced by that when I lived in Boston, and I would go see that all the time.

EC: What are some of your favorite musicians?

Saporiti: When I was in Boston, as a [college student], I used to go to the symphony every week and the BSO because they had a student card, so you go every Thursday for like 25 bucks a semester. I remember I saw this piece, Hector Berlioz is the composer, and he wrote a piece called “The Damnation of Faust,” which is this overwhelming three choruses based on the Faust mythology, and that’s one of my favorite pieces of music of all time. And then I also love the rock and roll or hard rock I grew up with like Rage Against the Machine and Weezer and Nirvana and all that grunge stuff. And then my dad’s record collection, The Beatles, Beach Boys, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Bob Dylan.

I like all that very entrenched, canonized stuff, but my favorite experiences are just hearing someone in front of me play an instrument. It doesn’t even have to be a particular piece of music. It’s just like, if there’s a clarinet player in an Italian restaurant, I’m always drifting out of whatever conversation I’m in to hear just the sound of their instrument. I’m really appreciative of live music because there’s just something so captivating and infinite in that very small experience that you can’t get with recorded music.

EC: Your music is rooted in storytelling. How do you use different sounds to tell those stories?

Saporiti: A lot of different ways. Sometimes it’s just textures of different instruments [that] might fit a lyric, you know, the difference between a plucked guitar with your fingers to a nice ethereal keyboard pad or something. I use a lot of samples, and I tell a lot of stories that are based on my historic research as an academic – these histories of Asian American folks and refugees and immigrants mostly. I sample from my field research sites, so if I go to an old refugee camp or something, I’ll knock on the barbed wire or the wood, and then I’ll turn that into a drum kit. So that’s what you hear on my recorded music to try to use the textures and real audible sounds of history inside the records themselves.

EC: What has your experience been like collaborating with your wife, Emilia, who directs and does lettering for your music videos featured in “One Day We’ll Go Home”?

Saporiti: Awesome because we want to be around each other as much as possible. That’s why we got married. I have found someone who I just love sharing my life with, and my life is so artistically driven, it would kind of be impossible for me to be in a full time relationship with someone if they didn’t share in that and vice versa. Like right now you’ve caught me in the middle of her law school exam final week, so I’m basically chauffeur and making all the meals and helping her study with flashcards and making sure the sleep schedule is good. So we look at everything we do as a team. And she’s a wonderful artist in her own right – a visual artist. She helps me produce the songs that I make as well. She sings when we perform live. She also has sewn this incredible stage jacket I wear in one of the videos which has hand embroidered little stories from my Vietnamese American childhood on it.

EC: Tell me a little bit more about the songs you included in “One Day We’ll Go Home” and what stories you are telling.

Saporiti: “Boat People” is in there and that is very central to the Vietnamese American story because I think most refugees or a good deal of us can trace their families where they directly came over as boat people. These folks who had to escape South Vietnam on these rickety little fishing boats. That song is taken directly from an archival interview of this guy who was a boat person who went to Canada. The lyrics basically tell this really cinematic story of this guy, Dr. Tran, who eventually made it to Montreal but he had to escape Vietnam, got into this little fishing, boat pirates attacked them, eventually made it to Pulau Bidong – this refugee camp off the coast of Malaysia. It’s harrowing, and I think that it’s really important to tell one story at a time as a teacher and also as a songwriter because it’s really hard for students or for listeners to take in a million people. You can’t understand that number, so boiling it down to telling these personal stories detail by detail, and then setting it to music, I think that’s a very emotional way to speak to this larger humanity issue of refugees and immigrants and movements of people – things that are happening right now in the Middle East, right now in Asia and Central America. This is just one person, but if you can empathize with that one person, then maybe you can empathize more deeply with the global issue of refugees and displacement.

EC: In conducting your field work, how do you go about talking to refugees when you’re working on new music?

Saporiti: I never talk to anyone with a goal of anything. I just explore and hang out and talk to people like people, and then if it comes up that they have an interesting story, and they share that with me, I might ask questions I’d ask anyone. If we’re having a drink at a bar, I would talk to everyone the same way, you know, just be a good hang. That’s something they should lead off with [in] anthropology classes, just be a good hang, don’t needle people to relive their trauma. It’ll come out if it comes out. And if it doesn’t, it doesn’t, and that’s all right. That’s something I had to learn when I first started interviewing people for my No-No Boy project. I was talking to a lot of people who used to live in a Japanese internment camp in Wyoming during World War II, and I would kind of right off the bat be like, “Tell me about the worst three years of your life,” which is a [expletive] up thing. Because, as someone who comes from some really harsh family history, you don’t want to define people by the worst parts of their life.

I’ve gone down and hung out in the Mexican camps across the border just to, especially as a son of a refugee, see what’s happening now and speak against it, tell people what I’ve seen, help out if I can. And it’s kind of up to [the refugees] what they want to share and just try to go in with a sense of reciprocity, giving something first before you take something away from them, which is their story.

I always bring down those Instax Polaroid cameras and just take pictures for people who have lost everything and having a picture of their kid means a lot to carry with them and then giving them the camera and a ton of film so they can take pictures of their friends. That little stuff, that can mean a lot, and then maybe you get some cool conversations and maybe that turns into art or songs, but that’s really secondary.

EC: Your song “Little Monk” on [your third album] Empire Electric is inspired by your experience at Blue Cliff [Monastery]. How does that experience influence your music going forward?

Saporiti: Pretty completely. My wife and I weren’t married at the time but we had started dating at Brown University. She had graduated with a sociology degree, and I could leave campus because I was a PhD student, and I had all my coursework done. And we just wanted to get out of there. When you’re 18 to 22, you’re never more aware. You don’t have mortgages to pay yet or kids to worry about, so that’s when the world really is spitting in your face the most, and you notice it, and you still have energy. Brown is a particularly liberal, progressive, activisty place, and it was so scary to be there at that point in time, because there were a lot of people just yelling about everything constantly and not really necessarily being informed about what they were yelling about. They were protesting everything but how rich those kids were, never protests about economic class but everything else, but with no substance behind it. I wanted calm in my life. I wanted the world to change. That’s why I went down to the Mexican border during a spring break to see these refugee camps for myself, instead of just yelling about what people were yelling about on Facebook. I wanted to actually go see for myself and see if I could actually help out.

The monks will sort you out because they just don’t buy into that because there’s greater truths for them. That’s not to say they don’t acknowledge there’s pain and suffering in the world. That’s what Buddhism is about. It’s acknowledging suffering and trying to overcome it in your life. I felt like I was just angry and I felt a poison in me from all the politics in the world, and all the suffering and [the monks] gave me tools to deal with that whether that was meditation or mindfulness stuff, just walking around. And yeah, that has sort of dictated my path. I don’t really use social media anymore. I’ll read the newspaper once a week instead of doom scroll constantly to see all the hell that’s happening because it’s not going to change in a week’s time. If I read one good article about the war over in the Middle East that’s going to be pretty thorough, and I’ll catch up on what’s happened that week.

I think what I learned is to tend to your own garden. I don’t want to yell about what’s happening at a southern border if I’m being an [expletive] to my friend that week. That’s something I can help. I can help being present and helping someone else that I know and love instead of abstractly spinning out because the world is on fire. And also checking my own privilege, right? I’m someone who has a PhD, and makes a living doing art. I have a beautiful wife, I have a roof over my head, which has not always been the case in my life and, talking about refugees, is not the case for a lot of people now. The monks really helped me check my privilege and get out of that elite campus protester culture. They let me empty out and see that life is still wonderful for some people. For some people it’s not, but for me, it is, and let me acknowledge that first and take solace and strength in that and then see how I can help the people in my community or if I do go somewhere where I can help.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.