Emilio Rojas: The Intersections Between Art, Politics, and Understanding

By Maddie Browning

A man carries a pillow across the U.S. for seven years. He sleeps on it every night, remembering when his uncle drew his last breath on the same fabric. It’s memory foam, a memory of his uncle and his wishes for his nephew’s future. This man is Emilio Rojas, a multidisciplinary artist and queer, Latinx immigrant with Indigenous heritage. His uncle convinced Rojas to follow his passion and not others’ dreams for him.

“My uncle died of cancer and made me promise that I was going to do what I wanted and not what my family wanted, so it kind of pushed me to just be like life is too short,” said Rojas. “My family was always like, ‘Oh you can do photography when you retire,’ and I was like, ‘Why am I going to do photography when I’m 70 when I can do it now?’”

He lost his uncle’s pillow in Texas and had to stop, but he continued his artistic journey with his uncle in mind. After his uncle’s death in 2007, Rojas dropped out of medical school and moved to Canada to study art. His work involves performance art with his own body, video, photography, installation, public interventions, and sculpture. When approaching a new project, Rojas starts with research, talking to people in the community, trying out new materials, or reworking older pieces by “reinventing or revisiting the past.” Before the official start of his artistic career, he always loved poetry and his first medium was photography.

Rojas performed his A Vague and Undetermined Place (a Gloria) at Emerson College on September 23 and 24. The performance involves a light blue paleta cart and Rojas dressed in an outfit to match. He asks members of the audience to draw what they think the U.S.-Mexico border looks like. He layers and projects all of the drawings on a lightbox to illuminate how vague the border is in people’s memories. In return, he offers them a paleta, a Mexican popsicle.

“It kind of gives me a moment to reflect with other people about the vagueness of borders, and people realize how unnatural they are and how just random,” said Rojas. “Like most borders are drawn by people who have never even visited those places. It’s these arbitrary lines that separate cultures and people and families.”

An Emerson class visited Rojas’ performance on the 23rd, and he noticed some students had trouble connecting to the performance. However, the last student to come up to the cart that day was fascinated. He was a first generation U.S. citizen whose parents migrated from El Salvador and Guatemala. They had actually crossed the border he drew for Rojas. “We ended up talking a lot more. The day felt a little weird, but just having him have that conversation and share that story, it felt like he was my audience for that performance,” said Rojas. “When you know someone feels it and has thought about it deeply, you have a moment to reflect together.”

Rojas said members of the audience like this student become much more. They are participants. Collaborators. The performance becomes an exchange of stories between Rojas and them. “My ideal audience is people in my communities, so people in queer communities and immigrant and refugee communities that feel the work in a different way,” said Rojas.

“There’s a lot of fear of the ‘other,’ which is kind of ignorant because of the drawing and them realizing that no one really knows what the border looks like,” said Rojas. “It’s short of humbling [that] we put so much effort into protecting this thing that is so vague and undetermined, like people cannot even draw it. If it was something that important, we should at least know the shape of it.”

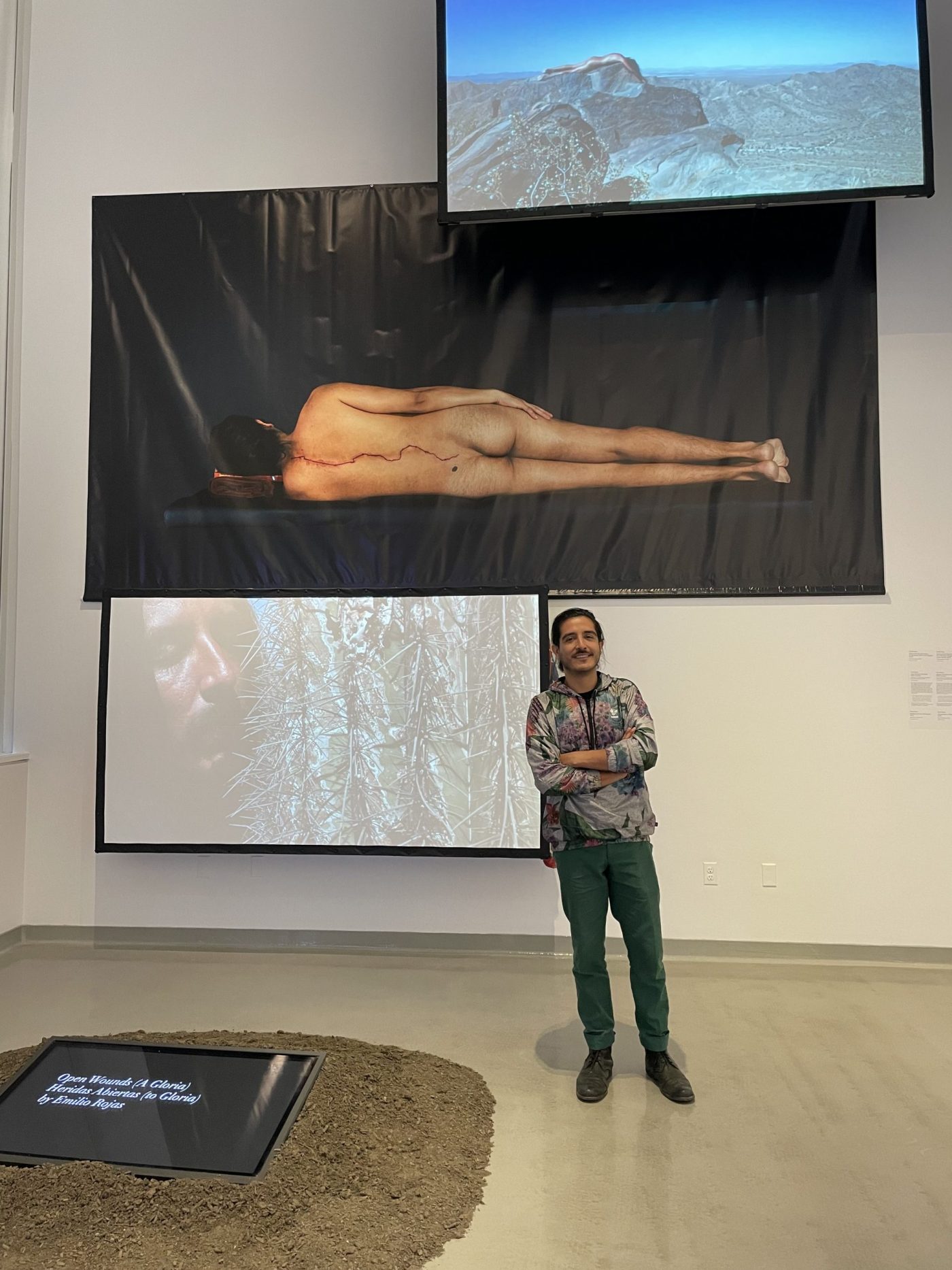

Roja’s tracing a wound through my body—displayed in the Media Art Gallery, as well as many other spaces across campus—has been in the works since 2019. With the help of curator Laurel McLaughlin, Rojas’ exhibition combines years of work that continues his examination of borderlands, trauma, and resilience. Emerson’s exhibition is only the second of seven to show over the next two years.

“Emilio’s work demonstrates an immense dedication to considering the nuances of liminalities—political, medium-based, or geographical nuances,” said McLaughlin. “His way of thinking with materials and gestures that step beyond neoliberal, heteronormative, and racial binaries continually inspires me and this survey collaboration.”

The opening on September 22 brought in 104 visitors who had a chance to speak with Rojas and share their interpretations of his work while learning his own. He hopes that people examine their own connection to the exhibition as well. Rojas said, “I want people to be able to reflect on this idea of trauma and throughout the exhibition, how does it relate to their own bodies and their own identities?”